#25 – Nine Days, directed by Edson Oda (USA) – Creative, powerful and affecting, Edson Oda’s NINE DAYS takes a metaphysical approach to examine what it means to live. Will spends his days monitoring a dozen of so TV screens depicting every action of a select group of people’s lives. When Amanda, one of Will’s favorites, a promising violin prodigy drives her car into a wall, either accidentally or on purpose, Will is shaken. While trying to understand what happened with Amanda, Will begins interviewing a series of souls who are each given the chance to live by being born into a human life. Only one of these souls will be selected after a series of tests that Will conducts over the next nine days. Will’s process is regimented but is thrown off not only by the impact Amanda’s death has had on him, but on one soul who behaves unlike any other soul he has interviewed in the past. His only support is Kyo, a rare soul who has never moved on to life on earth, but was granted a spot to help monitors/interviewes like Will to do their job.

Brazilian/Japanese Oda has fashioned an emotionally powerful debut feature, with a stark yet beautiful look, Will’s well-lived solitary home in a harsh desert landscape. The juxtaposition of otherworldliness, anachronistic technologies, like the VCR’s Will uses to monitor people’s lives, and the homey, mundane surrounding come together to create a strange, otherworldly atmosphere. In a beautiful touch, reminiscent of Hirokazu Koreeda’s magnificent AFTERLIFE, those souls who do not make the nine day process are granted one experience that Will creates for them before they are gone. There is one major flaw for me in the basic premise of the film, which if I dwell on for too long would ruin the meditative beauty of the story. Why would a man who is so broken be put in charge with the determination of a soul’s existence? It seems harsh and almost barbaric, coupled with the distasteful reality-show style competition these souls must endure. However setting that aside and just enjoying the film as an experience is truly remarkable, and it has one of the strongest, beautifully acted conclusions I’ve seen in a while.

#24 – Passing, directed by Rebecca Hall (USA/UK/Canada) – This assured directorial debut from actor Rebecca Hall reveals a practice that many people will be unaware. Set in 1920’s Harlem, a chance reunion of two high school friends poses moral and ethical challenges to a black woman who finds herself becoming entangled in the life of her friend who is living her life passing as white. I loved the performances in this film, particularly from Tessa Thompson who plays Irene. Thompson wraps herself in manners and poise, as a doctor’s wife who is living a life of means while nursing a fiery, intellectual passion for the civil rights of her black brothers and sisters. Her fascination with her high school friend Claire is mixed with revulsion at the way she endures the casual bigotry of her husband. From the opening moments of the film, where Irene herself, whether unknowingly, but more likely shamefully out of necessity, is shown passing as a white woman while doing some Christmas shopping, every movement, every glance, every tensing of her face is Thompson’s way of telling Irene’s story. It’s a masterful and restrained performance even as things start to unravel around her. Ruth Negga, ironically also first came to my attention through a Marvel production, this time television’s ‘Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.’ before showing her dramatic stuff in LOVING, plays the more flamboyant Claire with glorious abandon. She too hides a conflicting longing deep within, while living her life to the fullest, taking every advantage with seemingly little concern for her safety. She weaves a captivating spell on those around her, but conceals a quiet torment that sees her secretly envious of her friend Irene.

In addition to the beautiful character exploration of these two women, Hall captures a moment in time during the Harlem Renaissance, when artistry and intellectualism flourished in the black neighborhood on New York City. Where dances, and dinner parties flourished in the neighborhood, and questions of racial discrimination seemed distant, although limited in its geography. Costumes, settings, and the gorgeous black & white cinematography all support Hall’s fine directorial debut, where her strength is clearly from her background as an actor, and revealing the strongest performances from those acting around her.

#23 – Identifying Features, directed by Fernanda Valadez (Mexico/Spain) – This Mexican feature is a slow burn as a mother, Magdalena travels from her tiny village in Guanajuato to the Mexican/US border to find out what happened to her son. Along the way she encounters resistance, danger and mounting terror, as well as Miguel, a young man deported from the US who helps her on her quest. Throughout the film we must wonder whether the main character’s search is fruitless… all signs point to her son being dead. Director Valadez unspools the story slowly in darkness and visions of terror. But Magdalena finds herself similarly drawn to the plight of Miguel, who faces a tragedy potentially as large as her own.

Director Fernanda Valdez shows the grim determination in Magdalena, who only wants the truth, and the extraordinary lengths she will go through to find the truth. The bureaucracy, the horror, the uncertainty, but perhaps in helping Miguel, she finds another path. The incredible sound design that melds discordant music with droning sound effects underscores the terror that people are living through every day. The bleakness of the cinematography seems dark even in broad daylight. This devastating film paints a horrific picture of the challenges suffusing rural Mexico today.

#22 – Les Nôtres, directed by Jeanne Leblanc (Canada) – The English translation of the harrowing film from Quebec is OUR OWN, which darkly conveys the complicit nature of the tight community in s small town in Quebec. After a traumatic factory fire that is responsible for the death of a pivotal character, the town’s Mayor steps up, receiving accolades for supporting the town and creating a park in memory of those who died. One of his biggest supporters is Isabelle, whose husband perished in the fire, and whose daughter Magalie is the focal point for the film. Isabelle lives across the street from the Mayor, and his good friends with his wife, Chantal. Magalie is best friends with the older of two of the Mayor’s adopted, immigrant sons. When we discover that Magalie is pregnant, a victim of the manipulative abuse that is far too prevalent among young girls, we also discover how the tangled interpersonal relationships of those involved make this film all the more harrowing. It is not a spoiler to reveal that the abuser is the town’s Mayor, and his deft and sinister manipulation of Magalie make for some uncomfortable and horrific viewing. The townsfolk, already mistrustful of those who are different, look to the Mayor’s immigrant son, and in a devastating moment, Magalie’s frightened victim makes a decision that changes lives.

The film is tightly constructed and well-written, and if you find yourself getting frustrated with characters’ behaviors… that’s the point of Leblanc’s film. She co-wrote the screenplay with the actress who plays Chantal, whose character’s story arc is surprising and full of depth. The mother/daughter relationship shared by Isbelle and Magalie is remarkably realistic and adds to the frustration. It’s a small, quiet film, that one review i read criticized for not being more operatic due to its su object matter. I for one and grateful that it avoided that Hollywood-spawned pitfall and kept things low-key and simmering. The film also avoids a sunny ending, but keeps things firmly on the side or dark realism.

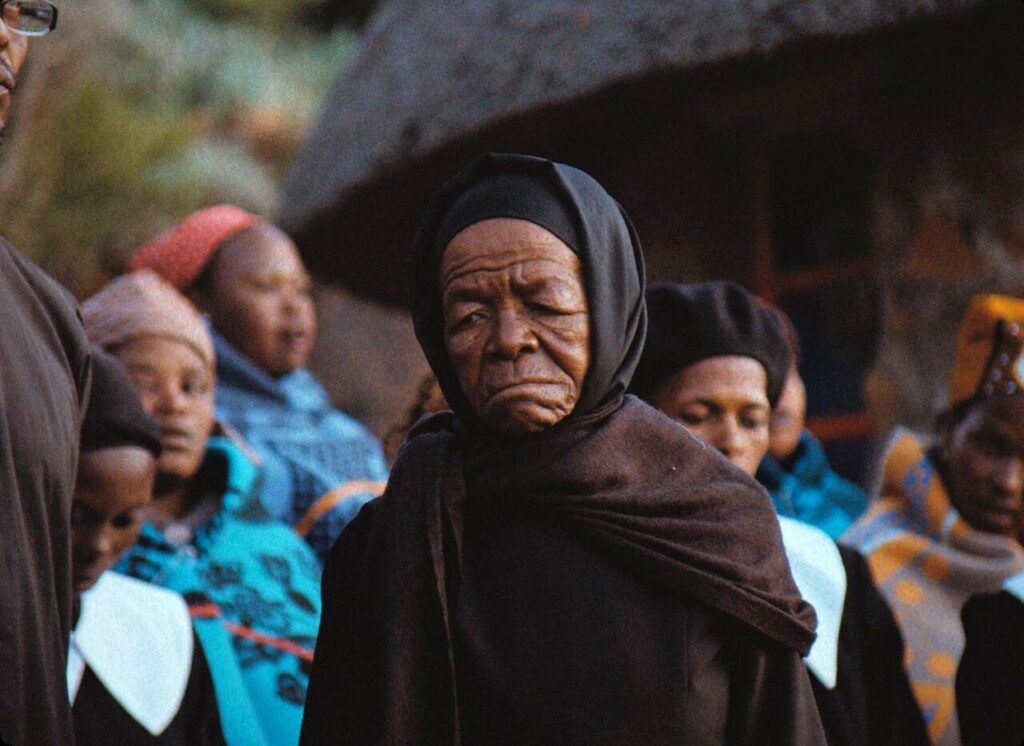

#21 – This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection, directed by Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese (South Africa/Italy/USA/Lesotho) – Mantoa is an 80-year-old widow who has lost everything. Living in a small village in the Southern African country of Lesotho, she has buried her husband, her children, even her grandchildren, and is just waiting to die herself, despite her strong health and indomitable will. When the nearby city officials decide to create a reservoir by damning a nearby river that will require Mantoa’s village be relocated, it ignites a fiery resistance within her and she begins a crusade to prevent the relocation, knowing that the burial grounds of her family will be left behind.

Lesotho director Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese weaves a powerful tale like so many other recent films about progress representing a death of the old ways. His camerawork, both illuminating the harsh but gorgeous African bush, and in close-up to Mantoa’s determined, age-lined face tell the story so effectively even with the scarcity of dialogue. Actress Mary Twala is the real key to this film’s success. Twala worked on dozens of films in her lifetime, and she sadly died at 81 last year, but this tour de force performance is quite a legacy to leave behind. Whether she is in despair at the loss of her family and her continued existence, or struggling against a faceless government whose only concern is progress. she is a forceful presence on the screen and you can’t take your eyes off her.