Relationships of all kinds are under fire in this batch of my Top 20. Whether it’s the complicated relationship that develops between a serial killer and an FBI analyst, a mother who will do anything in her power (or even beyond it) to protect her family, or a war veteran struggling with PTSD and a volunteer recovering dead bodies after a brutal war, relationships are at the heart of these films. It’s a tough group, but that’s how I like them.

#15 – No Man of God, directed by Amber Sealey (Canada) – I’m not a fan of movies about serial killers, and I have no interest generally, in getting into their heads to see how their minds work. However I was drawn to Amber Sealey’s NO MAN OF GOD, a film focusing on his last years in prison before he was executed, and the relationship he developed with FBI Analyst Bill Hagmaier, because a favorite of mine, Canadian actor Luke Kirby, played Bundy, and I was curious to see how that went. Elijah Wood played Hagmaier. Needless to say I was very pleasantly surprised at this film, which not only featured terrific performances, but was thoughtfully written and directed, to focus nearly exclusively on the two central characters and their relationship, and avoided any glorification of the heinous murders Bundy had committed. Much of the film is set in the interview room where Bundy and Hagmaier conducted their conversations, and many of these conversations played out like a cat & mouse game with each trying to draw the other out to play their hand. As the film progresses, however, you start to sense that some sort of relationship develops between the two, with Hagmaier possibly developing a deeper understanding of a man capable of committing such atrocities not being all that different than many other who never commit a crime, and Bundy developing a respect and even friendship with Hagmaier due to his honesty, and evident curiosity to understand him. It’s to Kirby’s credit that we are never quite sure if Bundy is genuine in this relationship, or if he is a master manipulator to the end. Still with hours to go until his execution, Hagmaier does get what he wanted: an admission from Bundy on many of the unsolved crimes he’d been suspected of.

Some have criticized the casting of Woods for being too youthful in appearance to play the FBI analyst, but I thought it worked well for the role. His large eye taking in Bundy’s storied, but just as carefully examining the mans every moves. Both actors play it low key, and Bundy’s occasional outbursts seem natural and well-handled. Credit must go to Sealey as well for her use of the female supporting or background characters, for representing, sometimes with just actions, the female point-of-view in this drama. Aleksa Palladino is strong as the defense attorney representing Bundy for his stay of execution and has a great scene when she explains why she does this to Hagmaier. Other women, such as a production assistant in a recorded interview between a clergyman and Bundy, convey their disgust and horror by simply staring stonily at him, flickers of emotion barely registering across her face while he speaks. Intense, dramatic, and very well handled.

#14 – Nomadland, directed by Chloé Zhao (USA) – Chloé Zhao’s follow-up to multi-Chlotrudis nominee THE RIDER is sure getting a lot of well-deserved acclaim. Zhao applies an inventive yet assured directorial hand in this melancholy tale about modern-day nomads, living out of their vehicles, traveling from place all cross, in this case, the American West. The story centers on Fern, played with the usual skill by Frances McDormand, a widow from the town of Empire, Nevada, that was basically eradicated by the shut-down of a factory that scattered its residents apart. Fern is making ends meet by living in her van and working for Amazon during the holiday rush, but when that ends, she finds herself at loose ends. She follows the advice of a woman she befriends in the RV park, who spends time in Arizona, with a nomadic guru. Fern is doubtful, but she travels there and discovers a community of like minds. Linda May (from whom she gets the tip), Swankie, David and the like. The film follows Fern for over a year, as she moves from place to place, making connections, finding herself briefly at her sister’s home, considering setting down roots with a new family, and ultimately making the decision to follow the path that is right for her life.

Zhao keeps things real in a number of ways. She fills the cast with actual nomads whose stories she tells, she keeps her direction direct and low-key, letting emotional moments burble up quietly with impact, reveling with her cinematographer, Joshua James Richards, in the beauty of our country, from the deserts of Arizona to the rocky terrain of the Dakota’s Badlands. She doesn’t try to make anyone feel a certain way, but allows Fern to make the decisions that are right for her. She adapted Jessica Bruder’s non-fiction book of the same name to tell authentic stories and they resonate strongly in the film. McDormand read the book and optioned it as a film, and her performance anchors it perfectly, and gives it it’s driving force, but it’s the three main supporting characters, Linda May, Swankie, and nomad-guru, Bob, who provide the authenticity as these non-actors play versions of themselves in the film. Truly powerful.

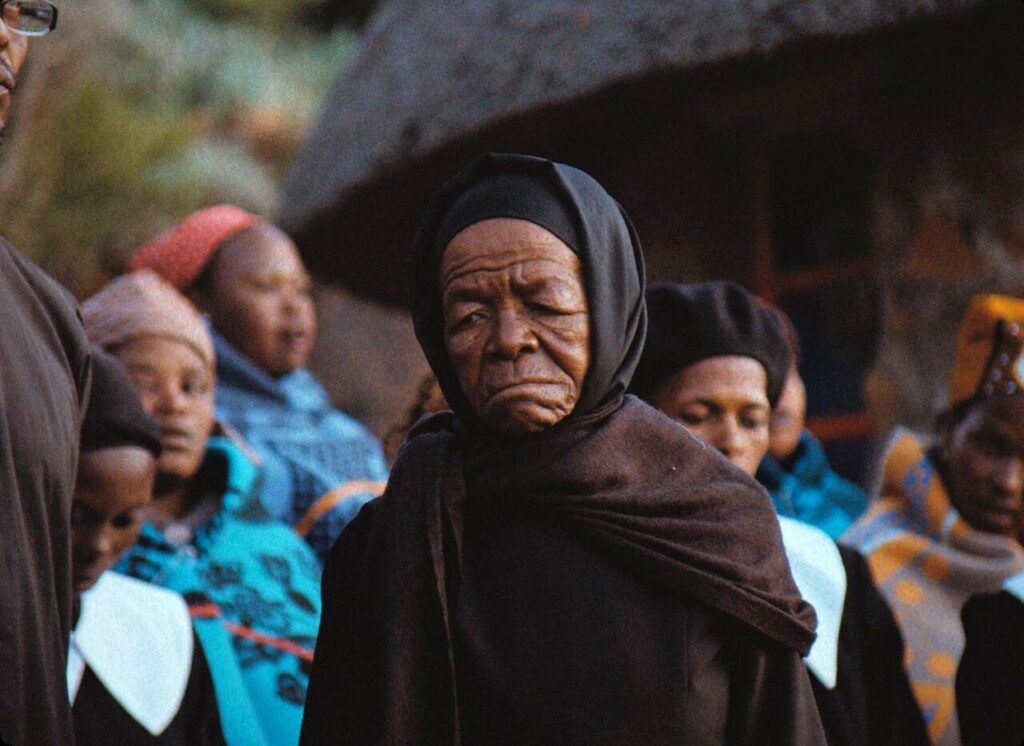

#13 – Quo Vadis, Aida?, directed by Jasmila Zbanic (Bosnia & Herzegovina, Austria, Romania, Netherlands, Germany, Poland, France, Turkey, Norway) – Films about the Bosnian War in the 90’s are pretty tough, and QUO VADIS, AIDA? is no exception. The story of a woman desperately trying to keep her family safe and caught in the middle of an increasingly hopeless situation is what we get with this film. Based on true events, it’s 1995, and the town of Srebrenica has been designated a safe haven by the UN The Dutch peacekeeping force assures the town that air strikes will occur if The Serbs try to invade. Instead, the UN leaves the Dutch out to dry and their base is overrun by Bosnian refugees fleeing the violence. Aida works for the UN as a translator for the Dutch Army. When her family, a husband and two grown sons, don’t make it onto the base after it reaches max capacity, and are left outside the locked gate with about half of the town, she desperately tries everything she can think of to get them in. She is ultimately successful, but that is only the first of a series of hardships Aida must face as the horrors of this war begin to escalate.

The film is very strong, with gripping direction by Jasmine Zbanic, who directed the haunting GRBAVICA: LAND OF MY DREAMS, which garnered a Chlotrudis nomination for its lead actress, Mirjana Karanovic. We know the story arc Zbanic creates is leading us to a devastating finale, but she keeps the tension high and hope, even just a slim strand, present. But you must see QUO VADIS, ADIA for the lead performance by Jasna Djuricic. Aida basically drags the viewer through this film, whether willing or unwilling. Her determination practically leaps off the screen compelling you to follow her on her desperate journey. There is no obstacle that she won’t try to sumount, no matter what the consequences. It’s compelling and powerful, but somehow she retains her humanity through it all, and Djuricic and Zbanic show this is small ways: a moment of respite where Aida gets high, a flashback to a happier time that reveals the guilt that Aida is feeling. Best Actress nomination for sure… possibly direction, movie, and editing.

#12 – Atlantis, directed by Valentyn Vasyanovych (Ukraine) – ATLANTIS is the Ukraine’s 2021 entry to the Oscars. A simple, straight-forward story that tells a grim tale set four years in the future with glimmer of hope in the form of love. While efforts are underway to keep Eastern Ukraine running after a particularly devastating war with Russia, there really isn’t that much left to salvage. Former soldiers Ivan and Sergei suffer from PTSD, and blow off steam with some target practice that escalates into a startling conclusion. The next day, Ivan commits an act that gets the factory they work at shut down. Sergei is a survivor though, and he gets a job delivering water across the blasted out, barren countryside because potable water is now incredibly scarce. On one of his sojourns he assists Katya, part of a project seeking to exhume the thousands of dead soldiers from the wars to identify and bury them. Sergei and Katya’s story starts off slowly but ultimately it’s the whole point of the film, and how even after the most damaging experiences there is hope.

Writer/director Valentyn Vasyanovych has created a film that is bleak and difficult to watch at points, but there are moments of sudden beauty as well. Vasyanovych acted as cinematographer as well, and his post-war landscape is as post-apocalyptic as any I’ve seen. The pace of the film is slow, with static shots and slow pans. The building Sergei lives in is a hollow wreck, and he seems to be the only person living there. Later in the film, an ecologist that Sergei rescued tells him that he needs to leave Ukraine, that the country is literally dead and will take decades if not centuries to become inhabitable again. ATLANTIS is really a tale about what could cause a person to chose to stay in that type of environment.

#11 – Test Pattern, directed by Shatara Michelle Ford (USA) – This chilling, or perhaps sobering film leaves quite a lasting impression. Renesha is out dancing at a bar with her girlfriends. Evan starts to dance with her at at the end of the night he asks asks for her phone number, which she supplies, much to her friends surprise. From there the unlikely pair embark on a lovely and sweet romance that starts with them learning about each other (she is a corporate drone living in an elegant apartment in a money-making job that doesn’t make her happy/he is a tattoo artist who has not drive to make a million bucks or take over the world, but is happy in his life) and moves to them committed to one another, buying or renting a cute little house together. Life and love seem pretty good for them, as two young people making it work in Austin, TX.

“All of that is mainly set-up for the main thrust of the film, which sees Renesha and Evan going to the Emergency Room to find a rape kit and report a sexual assault after Renesha spends a night out dancing at a local club with a girlfriend. In a sequence of events that play out like a horror film, the pair are shuttled all over the city trying to find a rape kit and someone who can adminster it, all while their relationship undergoes some intense testing. Without going into details, let’s just say that the film doesn’t end on a high note, but one that ponders the social injustices around gender and race and the how easily a trauma can upend a life or lives.

“Shatara Michelle Ford’s directorial debut, also written by her, navigates this excruciating experience with agonizing patience that results in a slow-burn drama filled with unspoken pain. Unspoken perhaps, but not invisible, as the body language of the two leads, particularly Brittany S. Hall’s Renesha is exquisitely displayed and tells a story that makes words unnecessary. Ford and Will Brill do a really great job with Evan as well, making him sensitive and loving, but also susceptible to the systemic racism and ingrained sexism that many straight, white men face. He’s a sympathetic character just trying to do do the right thing for the woman he loves, but can’t help stumbling in hurtful ways. Ford also plays with time, inserting a scene about 3/4 of the way through the film that makes you pause to place it in its proper moment, that illuminates the ongoing storyline to devastating effect. There are interesting parallels between this film and last year’s Chlotrudis Awards Best Movie winner, Eliza Hittman’s NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS in the way it examines the societal and systemic problems with women’s healthcare, particularly for those with less privilege (black women, and underage women).