We’re almost halfway through the year, and I’m finally getting to my Top 5 films of 2021. Yes, it took me more than a couple of months to deal with the errors I was getting from my web host that prevented me from doing so, but that’s finally done and I’m back for my irregular, sporadic posts.

Most notably, and personally, somewhat disappointing, is the fact that my Top 5 films of 2021 are all directed by men. While there are many films directed by women throughout my Top 50, including 4 in the Top 10 alone, it speaks to me of the disproportionate amount of films still directed by men. That said, none of the men who helmed films in the Top 10 are from the U.S. We’ve got Scotland, Japan, Malaysia, and Iran represented among these directors, all of whom bring a decidedly international view of life in their films. The tones of these films vary greatly, from the reflective calm of Tsai Ming-liang’s offering, to the hectic chaos from Sion Sono. The sense of alienation and dislocation suffusing my number one film is so reflective of the time and the world today, I’m not surprised that it resonated with me so strongly.

#5 – Red Post on Escher Street, directed by Sion Sono (Japan) – I can’t quite remember why I selected this fim as one of our weekly film discussion films, especially since director Sion Sono was known more for his over-the-top sexual and violent content in his previous films, which I tend to shy away from. I must have read or heard something intriguing that prompted me to give this 148 minute movie a shot.

It’s been a while since I’ve seen a film that just grabbed me by the lapels and shook me, taking me completely by surprise, making me cry and laugh simultaneously with the ballsy abandon of the batshit crazy, but technical marvel of Sion Sono’s RED POST ON ESCHER STREET. A famous and well respected indie filmmaker is tapped by a major studio to make their next film, hoping he will bring some respectability and festival award to their mainstream work. Director Tadashi decides to use non-actors to fill out his massive cast that includes dozens, if not hundreds of extras. The announcement of auditions in the small town sends a variety of folks, from an amateur theatrical company, and a devoted Tadashi fan club, to a grieving widow and a young woman who may or may not have murdered her husband into a bit of a tizzy. Add to this crew the meddling studio executive, and the director’s ex-girlfriend and the story moves along down unexpected paths. The whole thing clocks in at nearly two and half hours, but I wish it went on even longer.

There is lots of humor in this film, but lots of drama as well. The underlying message of the film is a strong one, captured by the use of such a huge cast of the role of the extra in a film. The final 20 plus minutes are a feat of filmmaking that astounds, even though we’ve probably seen the like dozens of times. ESCHER STREET director Sono has a major festival fan base, and is known for his gruesome horror films, and borderline pornographic sexual examinations. I have yet to see any of his other films, and they don’t necessarily sound like they’re my cup of tea, but if RED POST ON ESCHER STREET is any indication, I just might have to try another.

#4 – A Hero, directed by Asghar Farhadi (Iran/France) – Asghar Farhadi is the master of the ethical quandary. His complex stories put people in situations where they just can’t win, whether they are trying to do good, or acting in their own self-interest. And that’s the real beauty of his writing: there are really no villains… no bad guys. Everyone is just thoroughly human. On a weekend furlough from prison for defaulting on a debt, Rahim and his lady friend Farkhondeh try unsuccessfully to turn in some gold coins that she found for cash to pay off his debtor. Unfortunately, there isn’t enough to cover the debt, so Rahim decides to do the right thing and see if he can find the original owner of the coins.Tis decision sparks aa chain of events that turn him into a hero. Throughout the film, Rhaim exhibits the agonizing movie trait of consistency making the wrong decision, or letting others make the decision for him. Those around him, whether his son, his girlfriend, his debtor, the prison official, or a charity that help to raise money to cover his debt to get him released from prison, all have their own motives for their actions, the the complicated web of motivations only serve to put Rahim in a more and more challenging position.

“How Farhadi manages to spin this complex tale while (mostly) avoiding contrivances for the sake of the story is nothing short of masterful. Amir Jadidi embodies Rahim with an easy, soft-spoken charm, reeling you in to root for him even as you shake your head as he gets himself deeper and deeper into a bad situation. Stone-faced Mohsen Tanabandeh portrays the unforgiving debtor with strident conviction, but not without humanity, elevating him from the vengeful victim, to something much more three-dimensional. Sahar Goldoust brings a lot of motivation and nuance to the often thankless role of the girlfriend, helped by Farhadi’s integration of a mini storyline exploring Farkhonheh’s challenging family living situation, and the rigid societal conventions in modern day Iran.. In addition to the human exploration, Farhadi also explores the motivations and complexities of institutions like the prison and the charity. How he is able to integrate all of these many nuanced perspectives and motivations in under two hours is nothing short fo masterful. Sound design and cinematography are top notch as well, as you feel as if you are on the busy streets of Shiraz, amidst the shops and traffic. A HERO is his best work since his award-winning A SEPARATION, and that’s saying a lot since his output since then has all been terrific.

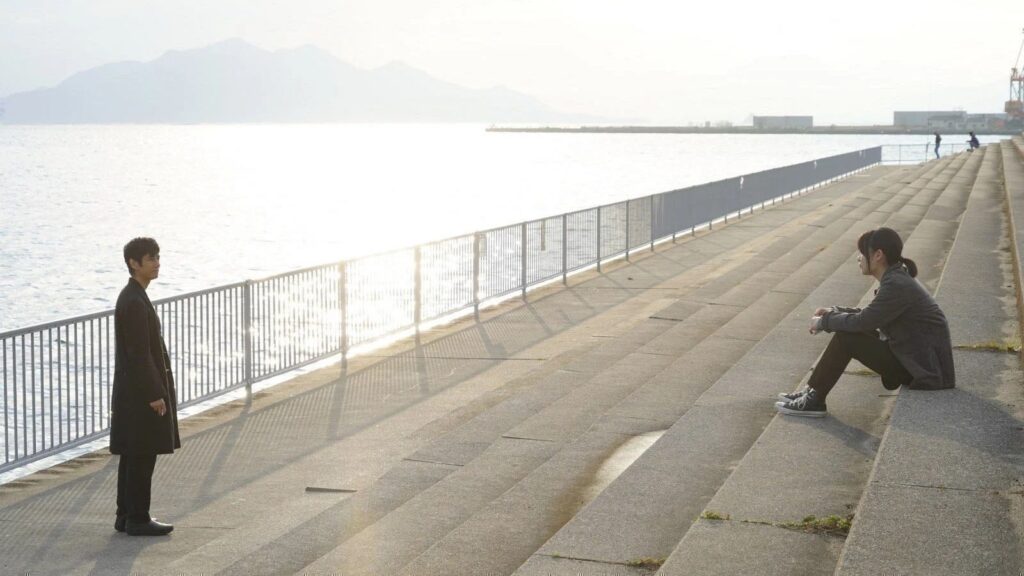

#3 – Days, directed by Tsai Ming-liang (Taiwan/France) – I’m continuously amazed at how music I enjoy Tsai Ming-liang’s films, no matter how opaque or glacially-paced they are. After seeing his documentary, AFTERNOON, I’m beginning to think that the themes Tsai explores emerge from his leading man, Lee Kang-sheng’s life. DAYS is rather interesting because it was pieced together from footage that Tsai shot when Kang (the actor) traveled to Bangkok to seek relief from an affliction that sent shooting pains through his neck. He also shot scenes of a new discovery for filmic inspiration, a young non-actor Anopng Houngheuangsy, preparing his meal with precise care, washing the vegetables and fish that he then proceeds to cook. These two character do eventually come together, possibly meeting for the first time for a business transaction that turns into something else, or possibly men who see each other from time to time and have developed a rhythm to ease each other’s loneliness for a short time.

I recently went back to watch Tsai’s debut film, REBELS OF THE NEON GOD, and was surprised at the young, the then just over 20-year-old Kang appeared. It’s true, that while he still doesn’t look his 52 years, the actor carries a world-weariness in his face and body that was most-likely exacerbated by the debilitating pain he was suffering during the shoot. Also intriguing was the fact that Tsai use the actual hoe that he and Kang share in real life as the setting for Kang (the character’s) home in the country. The blending of random filmed scenes, and real life with a simple, yet beautiful story is nothing short of glorious. I know Tsai is slowing down his film output, and has claimed to be in retirement, but I do hope we get more visual storytelling from this intriguing master.

#2 – Drive My Car, directed by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi (Japan) – Sometimes a film receives so much critical praise because it just that good. DRIVE MY CAR, which writer/director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi adapted from the short stories of Haruki Murakami with co-screenwriter Takamasa Oe is one such film. My experience watching the film was unusual to say the least, as two plus hours through the three-hour film the cinema lost power, and was unable to complete the film that night. I was able to return the following day to finish the film, but arrive about 30 minutes before the film had cut out the night before, and allowed me to really examine the subtleties and complexities of Hamaguchi’s filmmaking. I think it heightened the overall experience for me.

The story revolves around successful stage actor Yûsuke Kafuku who enjoys a fulfilling relationship with his wife Oto, who writes television series. The two are comfortable together, and enjoy a unique sex life in which Oto relates complex stories as she nears orgasm that evolve into scripts for her shows when Yûsuke retells them to her the next morning. Five years after a startling tragedy that reshapes Yûsuke’s life, (and prompts the opening credits, 45 minutes into the film) he is invited to a theater festival in Hiroshima to direct Uncle Vanya, the play that found much success years earlier when he played the title role. Yûsuke has chosen to stay in a hotel an hour away from the theater so as to listen to the script being read while driving in his beloved red Saab. He is bewildered and put out to discover that contractually the theater festival must utilize a driver to chauffeur the director back and forth. Twenty-three year old Misaki Watari is the scrappy, young woman who works as Yûsuke’s driver, and gradually the two form a trusting bond that is unknowingly spurred on by their respective grief, each having undergone a traumatic family experience. The rehearsal process begins, and Yûsuke ends up casting Kôji Takatsuki, former TV star who worked on one of Oto’s series, and was her lover. Kôji is unaware that Yûsuke is aware of this fact, and the two form a rather interesting bond that informs each of their personal directions.

There is so much that happens in this film, both story-wise and visually that it’s difficult to adequately review the film. but suffice it to say, the three hours go by easier than many films half its length. Cinematically, the scenes of Yûsuke and Misaki driving through Hiroshima and beyond are gorgeous, utilizing tunnels, bridges, intertwining highways and stunning landscapes to full affect. Hamaguchi even makes a massive garbage disposal plant a wonder to behold. I can’t really think of a category that I couldn’t nominate this film in, but I certainly won’t be neglecting the craft the films editing, use of music, sound design, and cinematography, as well as the acting. Misaki Watari is reminiscent of a young Bae Doo-na, and Hidetoshi Nishijima’s Yûsuke is stoic to the point of robotic, until that stifle emotion comes sputtering to the surface in a scene that is getting me choked up now just thinking about it.

#1 – Limbo, directed by Ben Sharrock (UK) – I’m quite intrigued by young filmmaker Ben Sharrock. Ben’s sophomore feature film LIMBO, was awarded the Cannes Film Festival ‘Official Selection 2020’ label before having it’s World Premiere at Toronto International Film Festival, followed by a European Premiere at San Sebastian IFF where it won the TCM Youth Jury Award. It’s an adeptly written, beautifully shot film about immigrant refugees awaiting word on their asylum requests in the desolate coast of Scotland. His first feature, the zero budget PIKADERO, is about a young, broke couple living in Spain during the economic crisis, looking for a place to consummate their relationship because they both live at home with their parents. Sharrock graduated from The University of Edinburgh with a degree in Arabic and Politics before attending Screen Academy Scotland, where he graduated with an MA in Film Directing followed by an Master of Fine Arts in Advanced Film Practice. It’s an interesting pedigree that he uses with distinction in LIMBO.

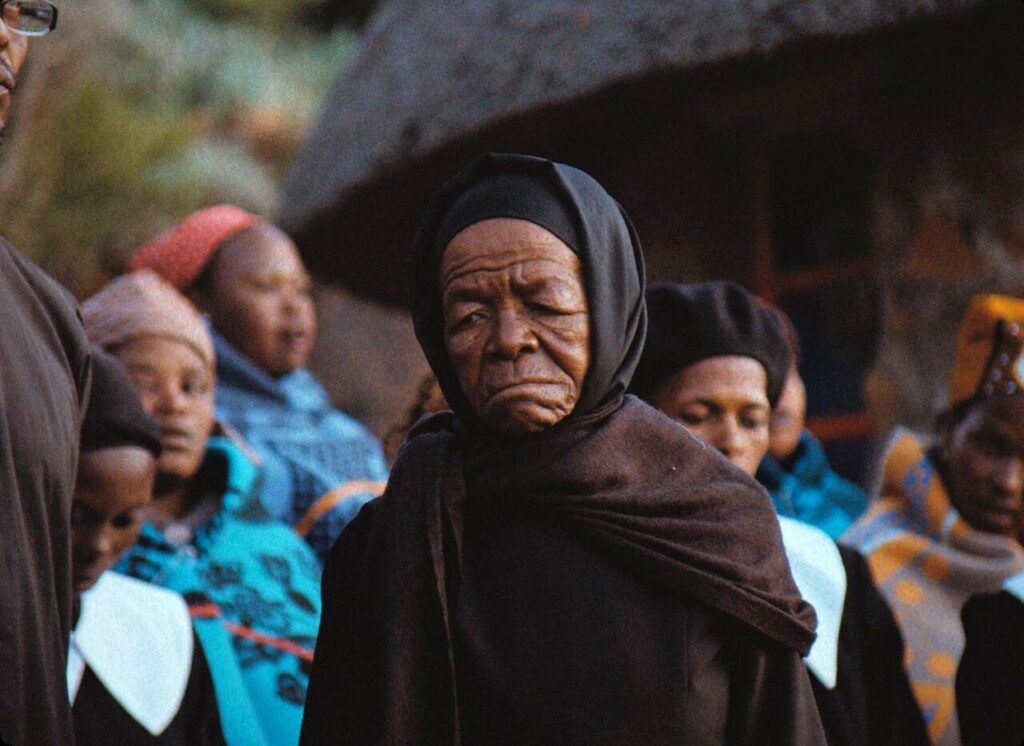

Omar is an up-and-coming Syrian musician who has fled his homeland to escape the devastating war. While he awaits asylum in Scotland with other refugees, he carries his oud everywhere he goes, but doesn’t play it. He speaks with his mother, also a refugee of Syria with his father, but far away. They all await news of Omar’s brother, who remained home fighting in the Syrian army. There have been several films in recent month about immigrant refugees, often trying to find a place in their new homes in Europe, Canada, the U.S. The gorgeous, but unforgiving landscape and climate of coastal Scotland are lovely representations of the separated isolation these refugees feel, without a home… in limbo.

Amir El-Masry gives a low-key but powerful performance as Omar. He’s got some big filmwork on his resume, including THE NIGHT MANAGER, TOM CLANCY’S JACK RYAN, and STAR WARS: EPISODE IX: THE RISE OF SKYWALKER. He’s got some great support as well, most notably as his roommate, Farhad played sensitively by Vikash Bhai, as the somewhat sad sack, yet optimistic comic relief, but with layers that slowly emerge with great affect. And what a delightful surprise to see Sidse Babett Knudsen, the star of the Danish series, ‘Borgen’ in an absurdly hilarious role as one of the Scottish instructors helping the immigrants acclimate to their new potential home. It’s writer/director Ben Sharrock who really shines here though, with that great combination of strong story, interesting, complex characters, and a deft eye.